When it comes to wildlife photography tips, the question I get asked most often is how to take sharp images.

There is no silver bullet, but over the years I have noted a number of factors that have contributed to soft images in my own wildlife photography.

What are the factors that affect image sharpness in wildlife photography?

- Shutter Speed

- ISO

- Depth of Field

- Long Lens Technique

- Focus Points

- Image Stabilization

- Tripod

- Gimbal Head

- Remote Shutter Release

- Wind

- Heat Waves

- Vehicle Vibration

- Calibrated Camera & Lens

- UV Filters

1. Shutter Speed

The first question I ask someone who tells me their images are not sharp is, “what was your shutter speed?”

You may be familiar with an old rule of thumb that states when hand-holding your camera the shutter speed should be equal to or exceed the focal length of your lens. For example, if you’re shooting with a 500mm prime lens you want your shutter speed to be at 1/500th or better.

I contest that this rule does not apply to today’s high megapixel cameras where the negative effects of camera shake are even more pronounced than the cameras of old. Camera shake occurs when a photographer accidentally moves the camera while taking a photograph. This causes an image to be blurry.

In today’s digital world, with 45MP cameras and larger being commonplace, my new rule for beginning wildlife photographers who are hand-holding their cameras is to double the shutter speed to focal length ratio where possible. Taking the same example from above, when shooting with a 500mm lens the shutter speed should be 1/1000th if the light is available to do so. With practice and good technique, you’ll learn to take sharp images with much lower shutter speeds but where possible use faster shutter speeds to your advantage.

I do wish to make the distinction between camera shake and motion blur. By definition, motion blur is the visual streaking or smearing captured on camera as a result of the movement of your camera, the subject, or a combination of the two. Wildlife photographers often use motion blur as a photographic technique to portray a sense of movement or speed. The image below was taken at 1/80th with the intent of portraying speed by displaying motion in the wings of this snowy owl. Take note, despite the slower shutter speed the eyes are sharp. That’s key to any great wildlife image.

WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHY PRO TIP: For freezing action with birds in flight, my go-to shutter speed for most birds is 1/3200th and even faster for smaller birds like a hummingbird. If the light is low this will require you to raise your ISO.

2. ISO

If fast shutter speeds are one of the factors for capturing sharp images you need to know how to adjust your camera accordingly. Increasing your ISO is one way that allows you to increase the shutter speed while maintaining the correct exposure. However, you need to be aware that increasing your ISO increases noise and noise reduces detail and thus sharpness in your images. Whenever possible, set your ISO to its base value, this is usually 64 – 200 on most cameras.

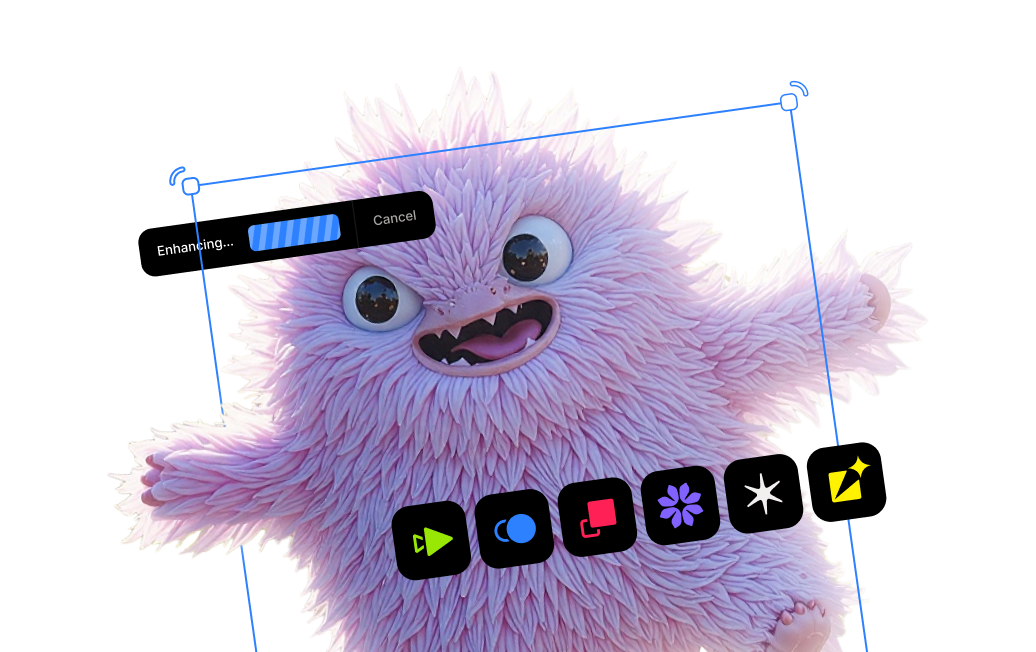

Wildlife Photography Pro Tip: You should run tests to determine the maximum ISO limit for your camera. This way you will know where the quality of the image gets so noisy that it can’t be recovered. Keep in mind that with Topaz Denoise AI you can remove a lot of that noise during the editing process. For images that require cropping and enlarging on the subject, there’s Topaz Gigapixel AI. This image of a mink was quite noisy and required a significant crop but rendered beautifully once processed with both Topaz Denoise AI and Gigapixel AI.

3. Depth of Field

Another way to increase shutter speed is to open up the size of your aperture as large as required to achieve the correct shutter speed. The nice thing is that playing with depth of field provides wildlife photographers with so much more than just creating fast or slower shutter speeds. Depth of field is one of the key elements that provide an opportunity for creativity in wildlife photography. Shooting lenses wide open at f/2.8 or f/4 provides an out-of-focus background and subject separation which focuses the attention of the viewer's eye on the bird or animal.

Be aware that racking out the lens to f/2.8 also makes for a very shallow depth of field reducing your margin for error in capturing a sharp eye. Stopping down your lens one or two stops not only provides you with a greater margin of error but many lenses render sharper images by doing so.

If you’re shooting birds in flight, you’ll improve your keeper rate by shooting at an f-stop like f/8 to make sure the eye and the wings of the bird are in focus. The trade-off is that your background will also be more in focus. Once your panning skills are up to it, I’d suggest you practice shooting wide open to capture those lovely soft backgrounds along with sharp eyes.

When shooting multiple subjects like this loon pair and their chicks, stop down to f/11 or f/13 to try and keep all eyes in focus.

Wildlife Photography Pro Tip: When shooting with a zoom lens, be mindful that sharpness may vary across its focal length range. Zoom lenses, especially less expensive ones, tend to get less sharp as you move toward the long end of the lens. Take the time to analyze your images at various focal lengths to make yourself aware of the focal lengths where your lenses are sharpest.

4. Long Lens Technique

If you’re shooting wildlife and birds, you likely have at least one long lens in your kit. Long lenses are prone to vibration which travels through the lens and to your camera which causes camera shake. The technique you use with your long lens is critically important to capturing tack sharp images. Take note of the image above of me shooting with my 600mm lens and note the following:

- The lens and camera are mounted to a solid tripod. Do not cheap out in this department, a good set of sticks is key to obtaining tack-sharp images.

- Place your hand and arm along the length of the lens to reduce the amount of vibration traveling down the barrel of the lens.

- Press your eye socket against the back of the camera. This will help to further reduce vibration. I've always found that the stock eyepieces on cameras do not allow me to comfortably press my eye against the viewfinder. When I purchase a new camera, I replace the eyepiece with an after-market eyecup.

- Use a slow rolling motion with your finger to depress the shutter button. Jabbing at the shutter button introduces additional vibration which results in camera shake and blurred images.

- The first image or two you take are when the most vibration is introduced as a result of you pressing down on the shutter. Taking bursts of images will help you to obtain a tack sharp image from a series.

WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHY PRO TIP: It’s always better to have a sharp image at a higher ISO than a soft image at a lower ISO. You can’t recover a blurry image but you can remove unwanted noise. Always use the lowest possible ISO that allows you to maintain the required shutter speed for the desired image.

5. Focus Points

Today’s cameras offer myriad focus options such as 3D tracking, wide area, dynamic, and so on. Many of these focus options cover a large area of the frame which broadens the scope where the camera can decide to achieve maximum sharpness. Single point focus selects a very small area and by placing that box on the eye of the subject you can guarantee that will be the sharpest part of your image.

WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHY PRO TIP: When time permits, achieving focus manually is a great option to ensure a sharp image. Many of today’s cameras have a feature called focus peaking which color highlights the area of sharpness in the EVF. This allows you to adjust your focus point accordingly to achieve maximum sharpness where you want it.

6. Image Stabilization

Today’s technology has come a long way. Every camera brand on the market has some form of image stabilization within the lens and/or camera that allows you to capture images at shutter speeds three to six times slower than you could have otherwise done without it. Nikon calls it Vibration Reduction (VR) and Canon calls it Image Stabilization (IS) and it can either be in the camera known as In Body Image Stabilization (IBIS) or in the lens.

Image stabilization is a welcome technology but you need to have an understanding of when to use it and when to turn it off. Not every camera brand’s system is the same so I recommend that you experiment for yourself. From my own experience with the Nikon system, I’ll provide you with some initial guidance on when I choose not to use image stabilization. This guidance varies by brand and with the camera and lens so it is debatable.

Turn Image Stabilization OFF:

- When you’re shooting at shutter speeds above 1/500th

- For shutter speeds slower than one second

- If you are shooting video with older lenses where the image stabilization motors in the lens make noise and interfere with the audio

- When shooting from a tripod

- If you wish to conserve battery life

I use image stabilization primarily when hand-holding in low light at shutter speeds under 1/500th. The system allows me to capture sharp images at speeds like 1/60th that would otherwise not be possible. For wildlife shooters, purchasing lenses with image stabilization is absolutely worth the added expense.

7. Tripod

You spent good money on a long lens and it is equally important that you invest in a well-made tripod. My recommendation is to get a good quality carbon fiber tripod with heavy gauge legs to provide the best stability and reduce camera shake. I recommend carbon fiber as it is more rigid than metal and does not make your hands as cold during winter shooting.

Choose a tripod that extends to a height that accommodates taller individuals and downhill locations requiring a longer extension on the front leg. I do not recommend tripods that have a center column. Extending a center column adds instability and wobble which is another factor contributing to soft images.

8. Gimbal Head

You chose a quality tripod and the same applies to the head you choose. A gimbal head performs magic, making it effortless to pan your big heavy lens smoothly in any direction for panning wildlife. I have found that a ball head is much more difficult to pan with and as such keeping the subject in the frame with a smooth motion is compromised leading to soft images.

WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHY PRO TIP: The knobs on your gimbal head that control vertical and horizontal panning are meant to be locked down tight only for transport. When shooting, loosen off the knobs enough so there is a slight amount of resistance, just enough so that the lens does not swing on its own without your assistance. Shooting with the knobs tightened introduces unwanted vibration through the lens leading to soft images. If you’re planning to shoot video, consider a gimbal fluid head for a much smoother panning of birds in flight and moving animals.

9. Remote Shutter Release

You may not think it but even the vibration from pressing down on the shutter is enough to create vibrations that can lead to soft images. This is especially the case if you are shooting in low light at slower shutter speeds. The use of a remote shutter release eliminates this vibration.

10. Wind

Take a moment to look again at the image of me with my long lens. Technique aside, imagine there was a healthy wind blowing from the direction this photo was taken. Between the camera, lens, tripod, and my arm that’s quite a bit of surface area for the wind to land on. All too often, the wind is an overlooked factor that creates camera shake which results in out-of-focus images.

The next time you find yourself shooting on a windy day keep these tips in mind:

- Remove the lens hood – You’ll notice from that image that the lens hood on the 600mm is quite large. By removing the lens hood, you significantly reduce the surface area that the wind has to push against.

- Get down as low as possible – Lower your tripod down as low as possible if the subject you are shooting permits it. Most tripods have a system that allows you to lower the tripod almost level to the ground. Not only does this reduce the wind factor, but it also gets you down shooting at eye level. For many wildlife subjects, this is the preferred vantage point for capturing winning images.

- Lower or remove the center column – Center column tripods are not great at the best of times but in the wind, their propensity for amplifying camera shake is significantly increased.

- Burst Mode – Taking bursts of images increases your keeper ratio whether it is windy or not. It’s a technique that I have employed in my shooting for many years. If it is a static subject you don’t need to shoot at 10 or 20 frames a second, use continuous low modes to shoot at 3-4-5 frames a second. I’m confident that you will be rewarded with more keepers at the end of a session if you start employing bursts in your shooting.

Below is an image I captured from a trip to Hallo Bay, Alaska. It is a tender moment between two coastal brown bear cubs on a very windy day. Unfortunately, upon closer inspection the eyes of the one cub are soft and that is the kiss of death in wildlife photography.

Fortunately, I can use the masking feature in Topaz Sharpen AI to apply sharpening to just the eyes of this cub and rescue this image.

11. Heat waves

Heatwaves are one of those things that are often overlooked as a cause for soft images. Heatwaves result when a heat source with a higher temperature relative to the outside temperature is between you and your subject. The longer the distance between you and your subject, the more impact those heat waves will have. Heatwaves are usually caused by the sun creating a heat source but not always.

You may expect to notice heatwaves only in the Summer however they are also present in Winter. I often see wildlife photographers using the hood of their cars as a platform for shooting. If your engine was warm or the sun is heating the hood you will have heat waves present that can lead to soft images.

Even having your lens hood on when your camera is coming from a warm environment to the outside cold can cause heat waves in front of your front element which can be enough to create soft images.

WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHY PRO TIP: Shoot at dusk and dawn, not only will you be catching the golden light but the sun also has less intensity which minimizes heat waves. Move as close as possible to your subject. The less air that light passes through, the less likely heat waves are to negatively impact your images.

12. Vehicle Vibration

I often find myself shooting out of my car window and I do so because the vehicle serves as a blind and the window ledge provides a stable platform. Attempting to exit the vehicle, even pulling over and rolling down the window can be enough to send some birds flying and critters running.

WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHY PRO TIP: When you spot a subject from your vehicle and are planning to pull over have your window rolled down in advance with your bean bag placed on the window frame and your camera on the seat beside you. Any additional noise and movement is enough to scare critters off before you can fire off a shot.

Vibration from your engine is the most common cause of blurry images. Most folks rest their lenses on the window frame for support. However, if your engine is still running the vibration will travel through the window frame and into your lens creating camera shake. I would suggest you take a few shots before turning your engine off as even that is enough for many subjects to flee. Once they appear to be accepting of your presence try turning off your engine.

I have found a bean bag to be the best choice for support when shooting from my vehicle, it provides more stability that the window frame alone.

13. Lens Calibration

We are now getting down into the fine-tuning aspects of things and this tip is one for those of you shooting with a DSLR. Most assume that when they buy a lens the autofocus is going to be accurate. This is rarely the case whether that lens is used or new out of the box. The chance of getting a perfect lens from the manufacturer is low and this is why I strongly urge you to have your lenses calibrated.

You can determine whether it needs to be calibrated by zooming in on an image where you know exactly where the focus point was and if you notice consistently that the image is sharper behind or in front of your focus point then your lens needs to be calibrated. This is referred to as front or back focusing depending on where the picture is sharpest. When I was shooting with a DSLR I calibrated each lens and camera combination including teleconverters to make sure things are spot on.

How To Calibrate Your Lens: There are three ways to perform lens calibrations as follows:

- Some camera manufacturers include a fine-tuning option from within the camera menu system. I have personally not found this to be the best choice, accuracy is all over the map.

- You can purchase any number of off-the-shelf software solutions. If you do plan to do this yourself, you'll need a laptop that you can hook up to your camera body so you have access to the software. And if you are calibrating a longer prime lens you need an area of 40 - 50 feet plus depending on the length of the lens. It is important to select an area for testing where the light does not change during your test and there are no heat waves or wind. Depending on how many lenses, camera bodies, and teleconverters you wish to calibrate this is going to take hours not minutes.

- From a time perspective, I preferred to outsource the job to a professional. Most professional calibrators charge per calibration, thus if I had two camera bodies, one lens, and one teleconverter, that would be four calibrations.

I'm going to leave it at that for now as the subject of lens calibration is an article in itself.

14. UV Filters

Let me say straight away, I do not recommend the use of protective UV filters on your lenses. Wildlife photographers pay a lot of money for premium optics in long lenses and it just does not make sense to then place an inferior piece of glass on top of the front element. It’s one more variable that has the potential to contribute to soft images.

If I can't convince you not to do it, at the very least purchase a quality brand name filter.

Conclusion

Learning to take sharp images requires you to be thinking about many things as you’re shooting, and not all will apply in every situation.

I recommend you spend the time to get to know your camera’s limitations and the sweet spot of your lenses as a starting point. Pay particular attention to shutter speeds, ISO, and focus points and you will have improved your chances of capturing sharp images by a factor of 10. Always remember to keep your area of focus on the eye(s) of your subject, that’s where your image needs to be tack sharp.

Turning your attention to sharpening during the editing process can make a huge difference to the sharpness of your images, even rescue an image you may have thought was headed for the recycle bin. Often times all that is required is a selective sharpening of the eyes of the subject. Fortunately, this is easily accomplished with Topaz Sharpen AI.

Now, you can take advantage of Topaz Labs' image sharpening right in your web browser. Try it now.