Article outline

- Introduction

- A cautionary tale of heavy-handed photo editing

- Cameras, sensors, and dynamic range

- White Balance

- Tone

- Color

- Conclusion

Admittedly, in my early days as a budding photographer, I considered myself a slider junkie. If a slider went to 10, I’d push it to 11. Subtle would not necessarily be the first adjective that you’d likely use to describe my earlier works, because I was fascinated with the wild and creative opportunities of digital post-processing. When I first picked up the camera with serious intent back in 1996, virtually all of the tools we take for granted today weren’t even close to coming to fruition, so post-processing wasn’t a big deal to me.

However, as more powerful photo editing tools came onto the scene, the novelty of one-click stylization presets had me smitten. It was a wild and crazy time, and I’m so thankful for experiencing it because it has allowed me to evolve my sense of style to appreciate subtlety and edit my photos so that the natural beauty of the scene speaks for itself. Before this evolutionary renaissance, it was clear that the bold stylization choices I made were driving the narrative of my photo, instead of the actual content of it.

Take a look at the previous photo of Crater Lake in Oregon. When you view it, you’d be more likely to notice the super-punchy contrast and crispy textures way before noticing the subtlety and nuance of the landscape itself that I also worked hard to capture. After several years, when the sheen of this aggressive stylization started to wear off, I began learning to appreciate the virtues and elegance of more faithful post-processing. As a result, my abilities as a visual storyteller grew and became more refined. I was paying more attention to the subject of my frame and not nearly as much to which filters I was going to apply.

Now look at the same photo that was processed with a more gentle touch. Crater Lake’s water really is deeply blue, but I didn’t want to bash the viewer over the head with over-saturating it. I also avoided over-processing the sky by reducing contrast and allowing the tones to take on a much more natural look.

The creative life cycle of a photo rests on your shoulders as the photographer. It’s your decision as to how you choose to represent it to your viewers. As I alluded to just before, the photographer I’ve evolved into chooses to share my photos as a faithful representation of what I originally placed in my frame while subtly infusing them with various creative elements. In other words, the first part of my post-processing deals with addressing some of the hardware limitations of today’s cameras—typically, around tonality and color—followed by making smaller global and selective changes to match the photo to my creative vision.

It may come across a bit extreme to refer to today’s ridiculously powerful cameras as having hardware limitations, but it’s true nonetheless. When I refer to the hardware limitations of today’s digital imaging sensor, I’m typically referring to its capability of capturing the tonal range of the scene on the business side of the lens. Despite the herculean efforts of camera engineers, cameras haven’t reached the point of batting 1.000 when it comes to nailing the correct exposure, white balance and color settings, and that’s why there’s still a clear need to correct and edit your photos.

Today’s sensors are still somewhat limited in how much of the tonal range (or “dynamic range”)—the shift from the darkest parts of the scene to the very brightest—it can capture in a single frame. Modern mobile phones employ software tricks where the onboard camera fires off a high burst of photos at varying exposures and merges them together to present an evenly exposed final result. In a lot of cases, this is an elegant and accessible solution for a wide variety of picture takers. The major downside is the lack of fine-tuned control.

However, as you climb up the camera market ladder, you gain access to all of the tonal data captured in the image. I’m assuming, of course, that you’re shooting in RAW. If you aren’t, then I highly suggest you reconsider, because you’re leaving a lot of critical tonal data on the table. You may be asking what all this talk about camera sensors and RAW file formats has to do with faithfully representing your image. The bottom line is that making even some mild tonal, white balance and color adjustments to the straight-out-of-camera image can pay back with massive dividends, and it’s as applicable to portrait photos as it is to landscape, nature and urban ones. The trick is to know when to say “when.”

To start, the three most elemental aspects of a photo that you always want to correct for are white balance, tone and color. Let’s begin with white balance. It’s easy to forget, but the truth is that virtually everything affects the temperature and tone of the light around you. Are you photographing in a room lit with incandescent bulbs? Did you notice the quality of light in the night photo you took under that streetlamp? And what about that neutral density filter that you have sitting in front of your lens?

Did you know that some ND filters can add a distinct colorcast to your photo? That is exactly what happened with the image below. I used a 10x ND filter to get this long exposure. The left 1/3 of the image is what was saved straight out of camera. The right 2/3 of the image has only one adjustment: correcting the White Balance. That’s how important this is.

Correcting white balance should be one of the first things you do, and that’s because white balance helps tell a story. A photograph of a skier that’s too warm doesn’t read right. Likewise, a portrait shot inside will seem incorrect if the light temperature is too cool. Light is part of the story you’re telling.

Next up is tone. Tonality plays a critical role in every single photo you take. The key difference is that your environment usually dictates how easy or difficult it is to capture its entirety. By “entirety,” I’m referring to your camera’s ability to capture detail in both the brightest parts of your scene all the way through the darkest parts. A scene with a high dynamic range means that the span between the brightest and darkest parts of your scene is wide.

The reason why I strongly recommend that you use your camera’s RAW file format is because it gives you complete, uncompressed access to manipulate all of that rich, tonal data. You simply couldn’t extract nearly the amount of tonal information in a JPEG as you could with a RAW file, and having access to that data can do wonders in making an overexposed or underexposed photo completely workable.

The final element that you’ll always want to correct for is color. I’m usually working on warmer or verdant colors because those are most plentiful while photographing the rainforests and waterfalls in the U.S. Pacific Northwest.

However, achieving correct color is critical when you’re talking about portrait, event and wedding photography. Ensuring proper skin tone should always be a consideration, as should other colors. Was the bride’s shoes a muted, creamy yellow or more of a vibrant sunrise color? Those little details can be very important, and it’s your responsibility to determine what the appropriate saturation and vibrancy needs to be, and where it should be applied.

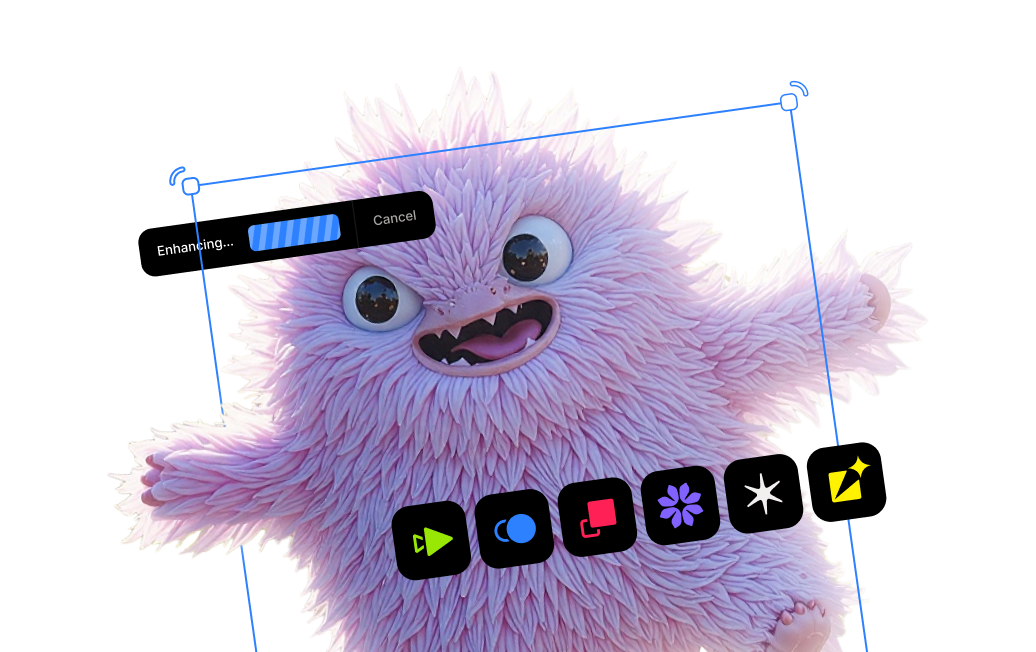

Which segues us to one last point that I’d like to make. Modern photo-editing software is so powerful and keeps getting better, faster and more capable as time goes on. Now you aren’t limited to what edits you can make, but also where you can apply them. This is where global and selective editing comes into play.

Global edits are those that apply consistently across the entirety of your photo. This is great when you want to add a quick boost of brightness or contrast. Selective edits are those that are confined to a particular area or element of your photo. It’s not uncommon to add a custom vignette over a person’s face so that the area surrounding it gets darker. This helps bring focus directly to the person’s face. You can also apply a graduated filter on an overly bright sky to darken it from the top down. These are considered spatially selective edits. You can also selectively edit your photo based on a particular element, like color. Perhaps you want to brighten just the greens or add saturation to the blues in your photo.

Today’s photo editing software makes it quite easy to do so. How far you choose to take the post-processing of your photos is completely up to you. After all, it’s your story to tell. My goal with this article is to make the distinction between your post-processing edits telling the story and the composition itself. Creativity can be applied just as effectively with a chisel as it can with a hammer.